The Buddha taught that disturbing emotions, such as anger, fear, jealousy, and attachment, are not to be denied or suppressed but recognized, felt, owned, and thoroughly processed. That process can take time and needs to be respected, but in the meantime, we can do significant harm to ourselves and others if we let strong emotions, especially anger in all its forms, govern our words and actions. Learning to see beyond a disturbing emotion, even in the midst of feeling it, allows us to act effectively, with clear focus and constructive compassion, and without collateral damage.

Below are a few suggestions for working with emotional turmoil based on time-tested advice from the Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. These can be further explored through such classic texts as The Jewel Ornament of Liberation and The Great Path of Awakening and their contemporary commentaries, and/or with the guidance of a teacher or mentor.

The process of taking power back from an emotional upset is presented in the Seven Points of Mind Training (slogan 44) in three steps, called the three challenges or the three difficult things: recognize it, get it under control, and stabilize it. This process is about cultivating our own peace of mind in order to see situations more clearly, act more effectively, and maintain compassion.

Step 1: Recognize and label the emotion. When we’re really caught up in an emotion, it can be hard to step back and simply recognize it as an emotion, rather than the external world actually falling apart. Maybe the world does seem to be falling apart at certain moments, and quite likely there really is something happening that has to be dealt with externally. But it’s the emotional distress that turns it into suffering and clouds our vision and ability to cope. Just take a moment to ask, ok, what is going on here in my mind? What is this thing I’m feeling? Oh, it’s anger. Oh, it’s anxiety. By stepping outside the emotion for a moment and reconnecting with our basic awareness, we loosen its grip, beginning the process of allowing it to dissolve. How to do this? With practice, we can gradually develop a reflex of taking a break and looking inward whenever we begin to feel emotionally upset. In Western culture, we’re often advised to count to ten before reacting. Or we could take a few deep, attentive breaths. That’s often all it takes to get enough distance to recognize the distinction between what’s happening externally and how we’re reacting internally. Being aware of this allows us to, as Pema Chodron puts it, “do something different,” which is the next step.

Step 2: Reassert control over your emotional state. This doesn’t mean we ignore it or suppress our emotions, but we can find ways to keep them from overwhelming us and leading us into words and actions we may regret when our mind is clearer. This step includes a number of techniques, which can be mixed and matched, depending on what seems most helpful in any given moment. If none of them feel helpful, maybe you’re not ready to work with it yet; or if you are dealing with underlying trauma, addiction, or mental health issues, you may need to seek out additional support for your situation, such as therapy, a support group, an organization like AA, or friends you can talk to.

- Change the channel. Interrupt the momentum of the runaway emotion by thinking about something else. Don’t worry! It’s not the same as suppressing our feelings. Strong emotions will keep coming back until they are ready to be fully resolved. We just keep alternating as long as we need to, using this or any of the following methods, at whatever intervals we need to, until we are able to operate again out of awareness rather than reactivity.

- “Drop the storyline.” There are many ways to interrupt an emotion, but they all depend on what Pema Chodron calls dropping the storyline. Strong emotions are fueled by endless chains of thought: reliving a situation, coming up with the crushing response you didn’t think of at the time, speculating about the future, what-if’s. The emotion will continue to grow as long as we keep feeding the thought process. It will naturally diminish every time we stop, even if it’s just for a moment.

- Relax your awareness, which is probably tightly contracted around what’s upsetting you. Notice the sky, let sensory input in (colors, sounds, smells, tastes, the feeling of a breeze or the temperature or the earth under your feet), let your awareness expand to fill space. No matter how bad things are, the sun is still shining and the stars are still twinkling in the vast sky (even behind clouds).

- Take a walk. Do some gardening. Go to the gym. Clean the house. Make some art. Get some work done. Cook. Any physical or alternative mental activity will help. As much as possible, let go of thinking and rest your attention in whatever you are doing. Follow your breath if it helps. When the emotion rearises, no problem, it needs to be acknowledged and felt; just interrupt it again as needed until it calms down.

- Remember impermanence. Everything is constantly in flux. Some things will never resolve completely, but nothing stays the same forever, especially our emotions.

- Remember it’s like a dream. The Buddha taught that everything we experience in life is in some way like a dream. Even if we don’t fully understand what is meant by that, it opens up more possibilities and spaciousness. Kenting Tai Situpa recently said in a teaching at PTC: “In a dream, you get sad, angry, or afraid. And when you wake up, it’s for nothing.” In the West, we often ask ourselves, how much will this matter tomorrow, in a week, in a hundred years? In the short term, it may be a crisis or a long slog, but sooner or later it will be over–and on to the next thing!

- Remember emptiness, which the mind training tradition calls “the ultimate protection.” Most simply put, we remind ourselves that no situation is limited to being the way we are seeing it in the moment. There’s always more to it, always other perspectives or aspects that we don’t see yet or may never see.

- Displace the emotion with love and compassion. We can do that with any negative emotion, especially anger or fear. If you can’t wish happiness or do taking and sending for the person you feel harmed by, then do it for someone you love, or for yourself. If we are engulfed in anger or anxiety, we can breathe in that distress and send ourselves love, compassion, healing, spaciousness, whatever will help. In Path to Buddhahood, Ringu Tulku tells us that anger and compassion cannot coexist. Just as heat displaces cold, compassion displaces anger. Again, this is not denying the distress, it is another way of interrupting its momentum, this time with a constructive emotion that points us toward our buddha nature.

- Let go of resistance and relax into the emotion. Once we drop the storyline, the most direct way to work with a strong emotion is to just relax and let it be, and explore how it feels. This is not an intellectual analysis, but just tuning into our feelings. Slowly scanning our body and noticing where and how the emotion is affecting us physically can be helpful–feel our heart racing, our chest or breath tightening, where we are clenching our muscles. And just sit with that, or walk with that. Breathe with that. What does anger/fear/sadness/attachment actually feel like? If the emotion is really overpowering, this may not be the best place to begin, but once its momentum has begun to flag, it is a very effective way to fully honor the emotion, tune into what it may be telling us, and allow it to run its course naturally.

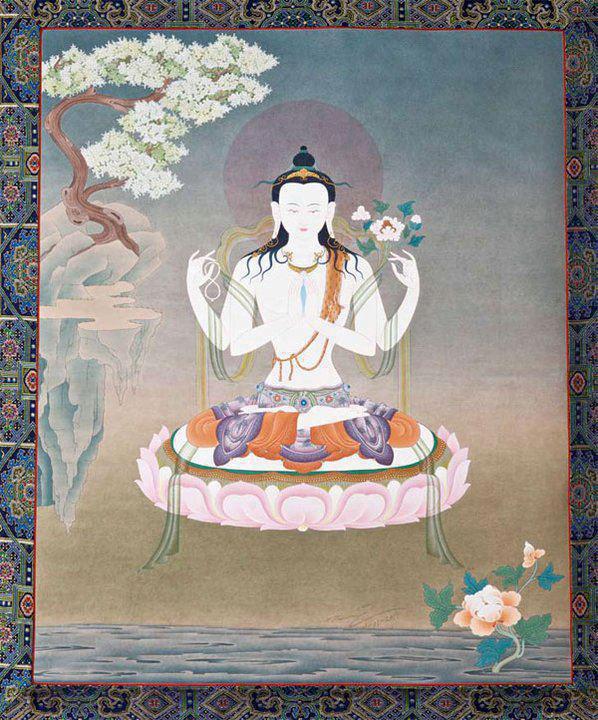

Step 3: Stabilize it. I won’t go into detail here but basically the more we work with our emotional distress in these ways, the less susceptible we are to losing our emotional balance in the first place. In addition, any dharma practice we engage in regularly will help strengthen and stabilize our awareness so we become less and less likely to get overwhelmed by emotions, and more and more grounded in equanimity (not in indifference, but in the ability to maintain awareness and clarity in the face of whatever feelings may arise). Calm abiding meditation, mindful activity, the four reminders, loving kindness meditation, taking and sending, mantras, Chenrezig practice, remembering the three refuges, prostrations, Dorje Sempa–whatever practices we have, the more we engage in them, the less power our emotions will have to derail us when adversity strikes.